Governance and engagement for climate adaptation in practice

Effective governance is essential for successful climate adaptation, and requires governments, institutions, communities and other stakeholders to work together to create policies that promote climate resilience. However, it is not easy to describe what good governance is, what it means in practice, and there is no universal consensus about its principles or criteria. As a reference, the World Bank was the first international institution to adopt the concept of good governance in the 1990s, while UN-Habitat launched a global campaign on Good Governance, indicating some key principles such as sustainability, subsidiarity, efficiency, transparency, accountability, civil engagement and security. More recently, United Nations defined 8 principles of good governance:

1. Participation

2. Rule of law

3. Transparency

4. Responsiveness

5. Consensus oriented

6. Equity and inclusiveness

7. Effectiveness and efficiency

8. Accountability

While identifying a set of criteria is useful for framing what good governance is, assessing how governance for climate adaptation works in practice remains challenging.

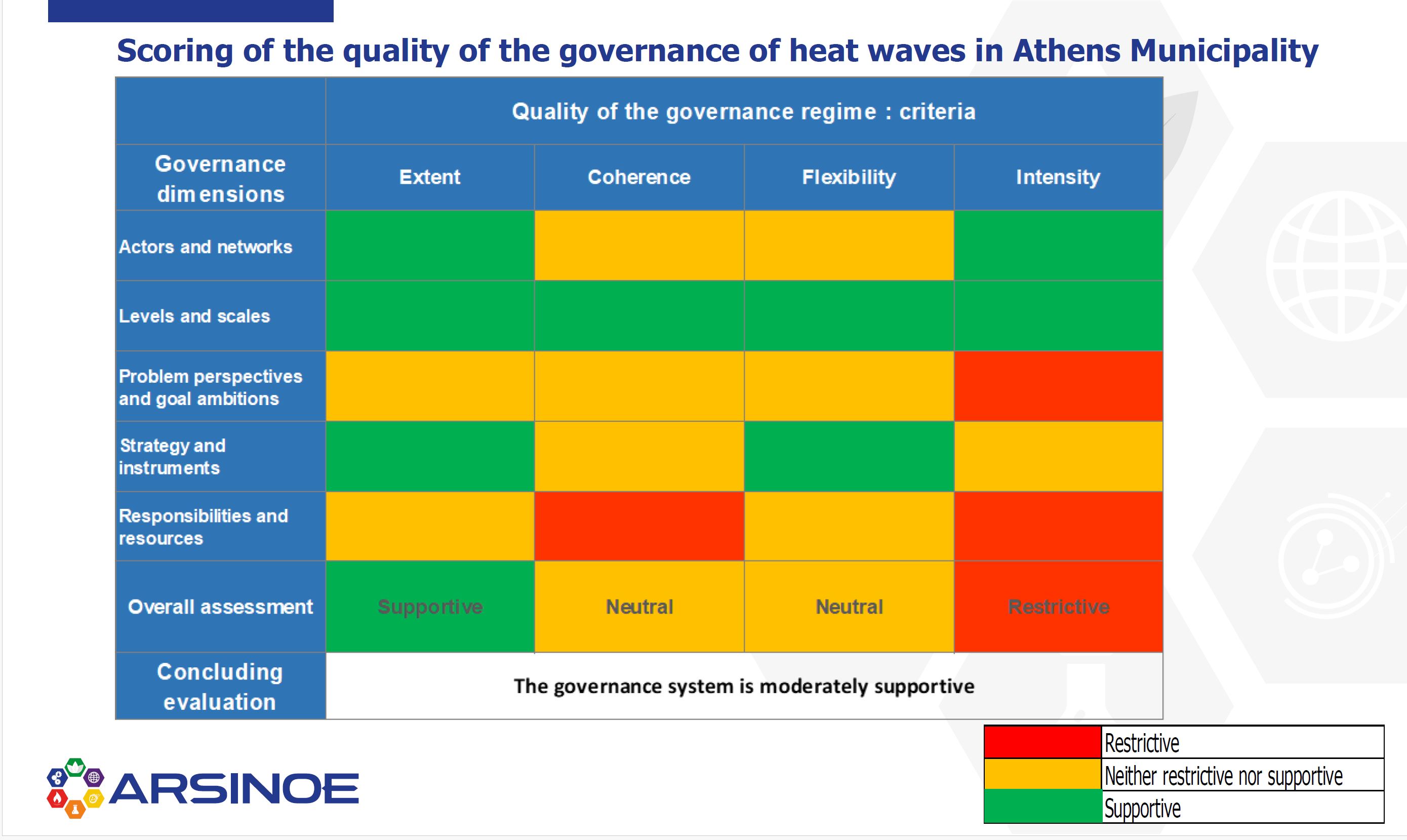

Governance Assessment of Heat Waves Management in Athens Metropolitan Area

This assessment (developed under the EU funded project ARSINOE) critically examines the existing strategies and policies addressing heat wave phenomena in the region. It aims to provide a diagnosis of the governance of heat waves at the moment of the project and discuss possibility of improvements with stakeholders. The study identifies key challenges, such as the need for improved coordination among agencies, enhance public awareness, and the integration of innovative technologies to effectively mitigate the adverse effects of extreme heat events. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of a cohesive governance framework, incorporating both scientific data and community engagement.

The assessment is based on levels of governance and 4 quality criteria. The five level of governance are:

• Actors and Networks

• Perceptions and goals

• Strategies and instruments

• Responsibilities and resources

• Levels and scales.

Four criteria were identified for a qualitative assessment of the governance of heatwaves:

Extent

Coherence

Flexibility

Intensity of Action

The analysis was carried out with a data collection based on desk research, literature review and interviews with selected stakeholders (24 stakeholders were interviewed). According to the results of the analysis, it emerged that earthquakes and floods were perceived as major risks compared to heat waves. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis of the governance highlighted the following aspects:

• Heat waves are managed centrally (Ministry of Health, Labour)

• Stakeholders involved in crisis management are not involved in the development of long-term strategies.

• Urban planning authorities are only limited to greening the city

• Water availability was not declared to be a concern

Positive aspects indicated include a flexible and dynamic heat waves management team (Heat office), a generally collaborative approach (especially during crisis), and the participation of Athens into international climate adaptation networks. On the contrary, barriers include the limited power of the Heat Office, limited coordination and resources, bureaucracy and low awareness of the population.

The conclusive assessment indicate that the governance is moderately supportive (especially in terms of involvement of different stakeholders) but has limitation in enabling and supporting changes

Citizen engagement in climate adaptation

An important component of good governance includes public participation and citizen engagement. It ensures public support, inclusivity, transparency and social acceptance of adaptation measures. However, citizens engagement can also be challenging and requires careful planning to ensure trust and legitimacy. The most recurring barriers that limit citizens engagement are: lack of time, impairments, lack of trust, low digital literacy, concerns about privacy, language, internet access, financial constraints, and education levels. Cities and local authorities often need more guidance in deploying methods and tools for citizen engagement. Critical issues remain how to engage the most marginalized and disadvantage groups, as well as how to maintain a sustained and effective engagement in the long-term.

Example: Living Labs

Several EU-funded projects with European cities often include planning and implementation of co-creation activities with local stakeholders. These often include activities such workshops, organized in different format and for different purposes. A way of consolidating local engagement is to establish “Living Labs”, intended as open innovation spaces to facilitate co-creation activities with and among stakeholders. In different projects, they assume a different name (i.e., city-hubs in REACHOUT) but underline the same principles of seeking bottom-up solutions through a series of co-creation activities.

Summary

Reflection

1. What are the main principles of good governance and how can it be assessed in practice?

2. Why is public participation an important component of governance for climate adaptation?

3. What are successful strategies and approach to engage local stakeholders and communities at the city level?